BY LUCINDA TOOMEY

Ahead of RRR in Conversation With…Ursula Burke this Sunday, Lucinda Toomey shares her thoughts on Ursula’s (Covid-19 interrupted) exhibition ‘A False Dawn’ at the Ulster Museum. This piece was written by Lucinda shortly after the exhibition opened in Feb 2020.

The premise of a Sphinx is a gate-keeper, a riddler offering seemingly conflicting ideas to any visitor in its path. From this initial confrontation with A False Dawn one immediately gets the sense that the myth of the Sphinx is of much greater significant, an overarching theme across the exhibition rather than a singular object in the space.

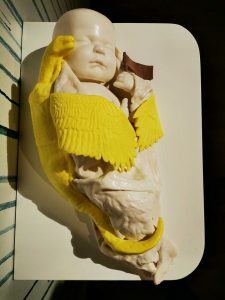

Drawn to the small, pale bundle off to the side of the room we discover a cradled infant laying peacefully on a shelf. Born is to me one of the most beautiful and confronting depictions of the legendary pull between nature

and nurture. Born as if already assigned a belief system, a set identity through nationality, the infant itself appears blissfully innocent as to the significance of what it may be holding or being held by.

It is impossible to know what the infant may be feeling or thinking, not purely due to its unconscious state but due to the tender nature of its age. It is only the viewer who may lay upon it their own preconceived notions as to what that nationality is, what it stands for and how it behaves; and is that not true of our own society at present? The nurturing grasp of the dragon-like creature, protectively encircling the child gives the illusion of security whilst the nature of the beast hints at a darker side, the danger of not complying with the plan set out for the infant.

Weaving through The Wounding it is difficult not to be affected. Intimacy is initiated by the positioning of the busts at visitors’ eye-level; the heroes have been taken off their pedestals. A humanizing of idols that brings a new rawness to the experience. Whilst the classical Roman and Greek inspiration is obvious, The Wounding feels incredibly relevant to today’s media environment. In the aftermath of the #MeToo movement, it seems almost everyone’s idol has been exposed; their ugliness, abuse, and scars all immortalized in history. The romance has been stripped from the legends, good has triumphed over evil but it has not come without serious and lasting consequences on those involved. In this aftermath, we cannot mask the survivors by glorifying their bravery whilst minimizing the pain they have been through. The brutality must be witnessed if it is to be truly understood and a better society built on the back of it.

In another juxtaposition, turning the corner one is introduced to another aspect of Burke’s artistry in the form of Embroidery Frieze – The Politicians. Despite being so highly regarded for her textile work, it is still rare for any museum to offer such extensive exhibition space for textiles. Traditionally considered the hobby of domestic ladies, perhaps used to fill the hours between visits from Mr Darcy, the art of embroidery has been elevated by

The Politicians is undeniably the most violent of the embroidered pieces, and also one of the most poignant. A swirl of hair as if in motion appears to blind its owner, at least temporarily to the goings-on around it. In particular, it eliminates from view the much more brutal act being enacted on another member of parliament only centimeters away. A man appears to be having his eyes gouged by an adversary, a more permanent blindness assumedly resulting. This idea of ‘blinding’ also present in the sunbeam-esque framing of the piece.

This thread of danger connects to The Pillow that lies almost like a crime scene in the middle of the space. I use the analogy of a crime scene because when standing over this piece, identifying each of the thinly veiled objects one almost has the sense of piecing together a person’s identity. It is perhaps this piece that presents the most complete rendering of a human being; their secrets, their lies, desires, and hopes for religious freedom or simple safe self-expression. There is a sense that the items increase in sanctity the longer they are

Placing Achille’s Heel in its own space, the accessibility and vulnerability that it is exposed to in this space is another striking confrontation. Typically such weak spots are hidden away, but here Burke has only chosen to

Burke’s choice to dress the foot in a style that showcases the unicorn motif provokes the idea that while each of us may feel afflicted with an Achille’s Heel of its own, it is as real as we believe it to be. The ancient Greeks believed in Achille as much as those living in medieval times believed in unicorns, as much as we believe in mythical weaknesses within ourselves.

Arguably the most haunting piece, the Augur, holds its own in its poignant solitary. The only creature to have ‘real’ eyes, and yet a fixed mouth and no limbs through which to express itself, it bears silent witness to the earth’s

graces and misgivings. The swaddle acting as much as a restraint as a comforting, protective shelter. There is no information given around the origin of the beam from which the Augur hangs but the nature of the material is to have its own past, a degree of ethereal independence that matches the Augur itself.

It could have been an overwhelming experience if each piece hadn’t been given just enough room to breathe. As it is, one is left with a sense of awe that is distinct for the confidence it instills that this exhibition will force change, because it cannot be witnessed without being internalised.

Words. Lucinda Toomey

Artwork. Ursula Burke