BY RIAN CONNOLLY

Whilst the children’s Pantos are held virtually and Belfast City mourns the absence of its annual Continental market, I read into our island’s Christmas customs in an attempt to get me into the festive spirit…

Christmas in lockdown won’t have the same magic as it normally does, but to some that won’t be much of a loss because it seems like there are not a lot of habits at this time of year for us to be proud of.

Pretending to have watched the Queen’s Speech or getting hammered on mulled wine and singing Fairytale of New York or All I Want for Christmas Is You at the top of your lungs are rituals for many, not to mention sharing ideas with other cultures and borrowing clichés from the movies. But beyond watching The Late Late Toy Show or going on a Christmas Eve pub crawl, it turns out that we do have some unique festive traditions in our heritage that go waaaayyyy back.

Daddy December

By the way, that is the literal translation for Father Christmas from the Irish Gaelic Daidí na Nollag, although children here might endearingly call

him Santy. And like in most Western Countries they can go meet the immortalised saint from Myra, Turkey at his grotto in malls and department stores. But this year make sure that you give St Nick a pint of Guinness (or a hot Whiskey) with his mince pie and carrot for Rudolph, that way he will definitely know he’s in Ireland. Don’t worry! Santy is automatically exempt from any drink-flying charges, otherwise who else is going to deliver all the presents?

Deck the Halls

Holly and ivy is an international must-have interior design trend for this season, and you can thank 19th Century Irish immigrants in America and beyond!

The notion of not having a Christmas tree in your home may be unimaginable nowadays (shoutout to Kevin McAllister in Home Alone 2) but long before Queen Victoria popularised the German decorative centrepiece in the 1840s, Irish families decorated their households with holly branches and strands of ivy. The custom goes back to pagan times when ancient Celts and druids considered Holly’s evergreen properties as sacred to warding off evil and offering a safe haven for the fairies. Whilst in Christianity its sharp leaves connoted Christ’s crown of thorns and red berries were likened to his blood.

Their accessibility was beneficial to the poor living in the rural Irish countryside, and it was also believed that the more red berries on each bough or wreath the more luck you would get in the New Year. Nowadays they come mostly in plastic and are arranged with lights and candles or spray-on snow for authenticity. Even a modern, chic alternative such as a dead branch or a piece of driftwood spray-painted gold with a string of LED lights wrapped around it would have the same effect; it’s all about bringing the nature and landscape from the outside indoors.

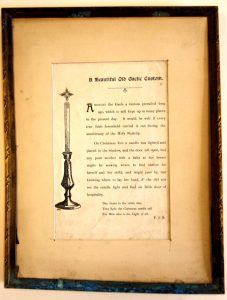

The Wanderers’ Candle

Like Holly, a glowing candle sitting in a windowsill behind frosted glass at the front of the house is another cosy finishing touch.

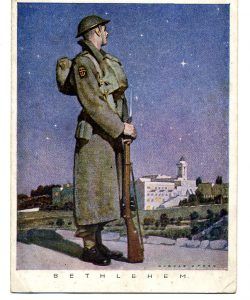

On Christmas Eve in the Republic of Ireland, a flame has a primarily biblical purpose to welcome Mary and Joseph upon their trip to Bethlehem. But at one point in history it was much more functional, for in the late 1600s the country’s penal laws ruled that Roman Catholicism wasn’t allowed to be practiced. Therefore the candle signified a safe place for priests to perform Christmas Eve mass. It was also a sign of welcome to the household for those in need of shelter and food, with a table laid out inside.

Shortly after she began her term in 1990, President Mary Robinson put a Tilley lamp on the window of her home in memory of the Irish immigrants abroad to sentimentally illuminate their way back to their homeland.

I predict that there will be candles and lamps lit this year for the Irish who cannot come home on account of the COVID-19 pandemic.

All play and no work

Masked men knocking on your door and entering your house on Christmas Eve will undoubtedly conjure up some worrying images… but this is likely to be part of a practice called ‘Mummering’ which was a lot more commonplace throughout the UK up until the late 20th century.

Mummers would go from door to door in silly costumes with blacked-out faces and perform plays and then request a donation of food or money, but nowadays they go into pubs and perform on the streets. Even my late grandfather used to write and perform ‘Mummy plays’.

St Stephen’s day (what the day after Christmas is called in the republic) is also known as Wren day, or Lá an Dreoilín. ‘Wren boys’ and men are the south’s equivalent to the mummers, only they wear elaborate straw headgear and recite a poem. The story goes that the wren bird betrayed St Stephen by singing, alerting Cromwell’s troops to Stephen’s whereabouts so that they could then kill him. Older customs involved hunting and tying a wren to a branch and parading it through town in vengeance, but fortunately this cruel practise is long gone. Wren boys demand payments to ‘bury the wren’, or more likely just buy the lads another round.

Icy dips all in the name of charity

We all know at least one person who will go on a festive swim in their Santa hat and not much else. Living on the North Coast I certainly know a few

and have even been tempted to take part myself for a good cause (…and maybe also for a hot Greggs sausage roll afterwards).

Christmas Splashes likely originated in England before the Anglo Irish brought it here where it is traditionally carried out in popular coastal spots such as Forty Foot on the Howth peninsula, Dublin.

Little Christmas

This is something my mum still practices, and it is a well-deserved rest for all that she does at this time of year. Being a predominantly matriarchal society in the ancient times, Irish mammies will go down in history as strong and ‘Little Women’s Christmas’ on the 6th January is their day off.

The woman of the house puts her feet up whilst the man does all the housework, prepares the dinner, and takes down all the decorations for January 6th as it is also considered to be the last day of Christmas. Might be a good idea to have a fire extinguisher at the ready though…

Mid-Antrim Museum Collection

And there you have it, some trivia to bore your relatives with over Zoom before the conversations begin to turn dreary and awkward. So, however you say it – Merry Christmas, Happy Holidays, or Nollaig Shona Duit…

Rian Connolly has written this blog as part of our Creative Writing 2.0 programme and you can read more published writing by participants in 2021. Photos provided by our local museum partners.